- Home

- EIDOLA

-

ACTIVITIES

Apri sottomenù

- EIDOLA's HUB

- Presentation of the Study Centre EIDOLA. Materiality, Cognition, and History of Religions

- International Conference Le Forme della Reclusione. Monasteri e carceri, October 10-11 2024, University of Bologna

- XXIII International Association for the History of Religions World Congress, August 24-30 2025, Jagiellonian University, Kraków

- Annual Meetings on Christian Origins - Italian Centre for Advanced Studies on Religions (CISSR), September 25-27 2025, University Residential Centre of Bertinoro

- CONTACTS Apri sottomenù

- Research

- Publications

- Agenda

EIDOLA

The Centre investigates religious phenomena, in all their social and cultural repercussions, on the basis of material data, from antiquity to contemporaneity, in a comparative historical-anthropological perspective, and in a constant dialogue with the cognitive sciences of religion.

The Study Centre EIDOLA proposes an approach to the history of religion that starts from materials rather than models, questioning the definitions traditionally proposed on the basis of traditional so-called 'sacred' texts. The focus is on objects and the forms of their circulation, a topic that has become the subject of increasing attention in the last decade.

Recent approaches from neurobiology and material culture studies open up different and stimulating possibilities for investigation: images, objects, spaces, but also movements and dances not only express emotions, thoughts and behavior, but at the same time construct, orient and condition them. Decisive in this perspective is the role of authority and institutions, certainly the official ones but also the informal and community ones, without which it is not possible to speak of religion and/or spirituality phenomena.

Maintaining a strong interdisciplinary perspective, the Centre engages with the perspectives of sociology, archaeology, architecture and physical anthropology. On this topic, recent publications include: Materiality and the Study of Religion. The Stuff of the Sacred, edited by Tim Hutchings and Joanne McKenzie (Routledge, Abingdon 2017); Religion and Material Culture: Studying Religion and Religious Elements on the Basis of Objects, Architecture and Space, edited by Lisbeth Bredholt Christensen & Jesper Tae Jensen (Brepols, Turnhout 2017).

Therefore, the following research topics are under focus:

- Material dimension of practices and rites, institutional and otherwise, in their symbolic and action value;

- Relational relationships between materiality, attitudes and beliefs;

- Perception, construction and use of spatiality starting from material aspects;

- Objects and places of institutions, authorities and power;

- Role and use of objects understood as mediators of the 'sacred' in iatro-mantic contexts;

- Role of magical-religious and affectionate objects in therapeutic and rehabilitative contexts;

- Mental representations and narratives of materiality as tools for the well-being of the person, from an individual and group point of view;

- 'Diaspora of the sacred' and derivatives of the religious dimension in the affective, emotional and relational spheres;

- Paths of heritagization and relationship with memory in exhibition and museum processes;

- Discursive strategies and performative practices in the construction and perception of the religious phenomenon;

- Interactional approach to religious language as a social event in the communicative, inferential as well as intentional context.

The purpose of the Center is predominantly scientific-analytical, in close coordination with teaching and field operations, also thanks to collaborations with institutions and companies. The primary intent is to promote research by offering opportunities for comparison and exchange of knowledge and skills on aspects and themes inherent to the materiality of religion in dialogue with the most recent socio-cognitive developments. This is a topic that has received growing attention in the last decade.

An essential component of the internal articulation of the Centre is the scientific and educational partnership.

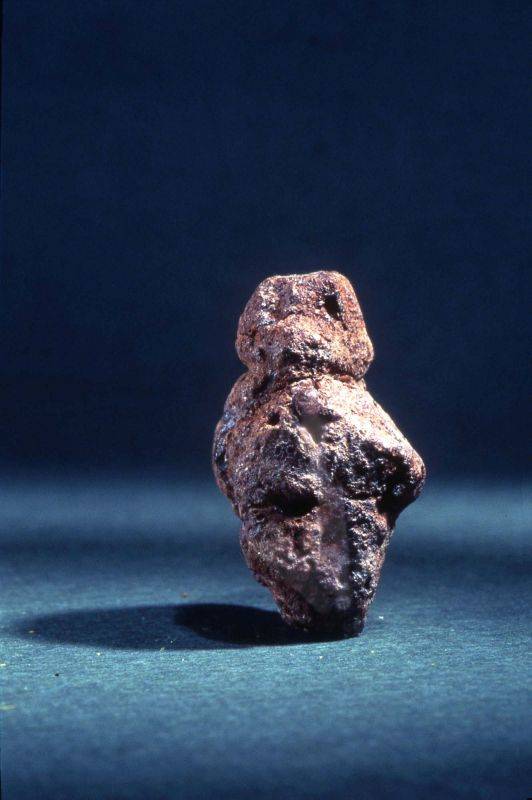

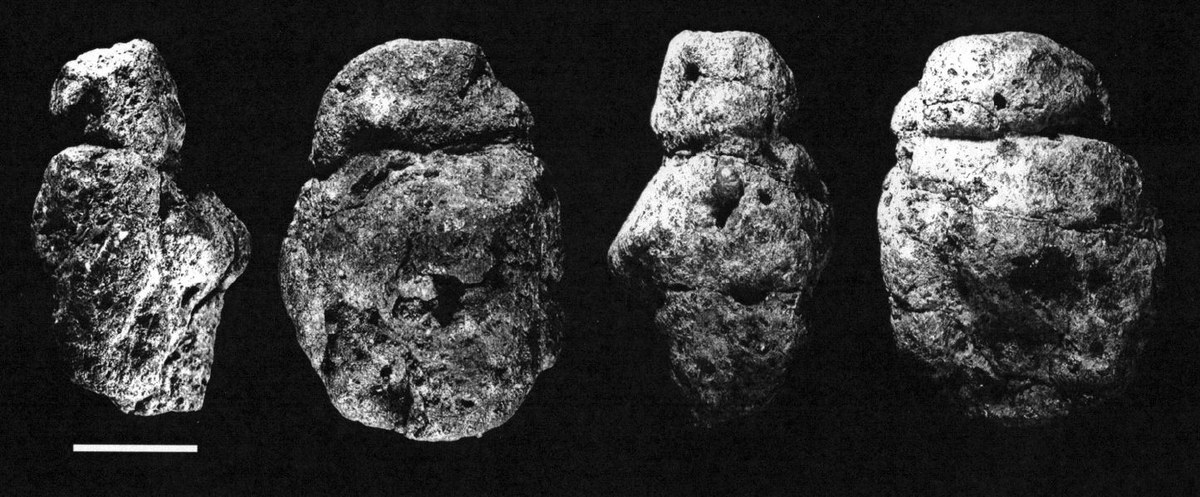

Photo: D'Errico F., Nowell A., 2000: A New Look at the Berekhat Ram Figurine: Implications for the Origins of Symbolism, Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 10, pp 123-167.

«1. What is the role of material culture in religion, historically, and prehistorically? What kind of phenomenon is religion? Is it a constant or has it changed – has it perhaps become more or less material, discursive, or intellectual with time? Is it basically ideas and beliefs taking place in the mind? Or is it basically a specific discourse, taking place verbally and in writing? Or – further – is it basically, or additionally, a material expression, supplied with discursive explanations? Is material culture basically an illustration of ideas, or does material culture also constitute these ideas? 2. What types of material culture characterize religions as such? What kind of architecture, burials, depositions, gear, statuary, and imagery, characterize the historical contexts, which we agree to be ‘religious’? If we have these material features in the prehistoric record, then do we also have religion? 3. Is it possible to identify religion (historical as well as prehistoric) on the basis of material culture alone? As it is today, definitions of religions are made on the basis of the study of texts and/or observation. When applied to prehistoric material these models run the risk of either not being able to say anything new about the material or of being anachronistic. From what point and place in (pre-)history can we speak about religion?»

(Lisbeth BREDHOLT CHRISTENSEN and Jesper TAE JENSEN, éds., Religion and Material Culture: Studying Religion and Religious Elements on the Basis of Objects, Architecture and Space. Proceedings of an International Conference held at the Centre for Bible and Cultural Memory (BiCuM), University of Copenhagen and the National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen, May 6-8, 2011, Turnhout, Brepols Publishers, 2017 [excerpt from Introduction: Working Questions])

«Most cognitive studies of religion adopt a modular theory of cognition. The 'space' that is studied is often the 'space between the ears'. Culture and religion are viewed as by-products of more entrenched features of our brains. Although this 'Standard Model' explains many intuitive expressions of religious belief, it has trouble explaining (a) the variability of religious systems crossculturally (b) the uses of material culture (i.e. symbolic structures etc) in transmitting religious concepts. The following thesis presents a 'wideware mind' hypothesis for religious cognition. I urge that while our internal cognitive architecture is causally relevant to religious cognition, the material artefacts of culture must be viewed as cognitive properties in their own right. Hence any causal account of religious cognition must acknowledge the external features of minds and how our neurological resources interact with the artifacts of our world.»

(David J. MURPHY, Sacred Technologies: The Evolution of Religious Cognitive Niche, MA Thesis in Religious Studies, School of Art History, Classical and Religious Studies, Victoria University of Wellington - Collection: Open Access Victoria University of Wellington, 2009. https://figshare.com/articles/thesis/Sacred_Technologies_the_Evolution_of_Religious_Cognitive_Niche/16967245)

«The need for the ethnographic method in the analysis of religious meaning emerges from the specific nature of that meaning. In popular religion, meaning does not originate in a set of propositions, a ‘theology’, but in a form of engagement with the world. This engagement might include different forms of communication whose performative component trumps their propositional contents. These forms of communication are normally defined as ‘symbolic languages’ when religious scholars try to translate them into explicit verbal statements, that is, into a set of propositions. Of all these modes of communication or symbolic languages, in this article I have focused my attention on sacred objects. These are objects with absent signifieds that evoke notions about the sacred, the divine or the supernatural. One way of approaching the analysis of sacred objects is by means of the extended mind hypothesis. What if such objects were instruments of thought rather than objects of thought? That would explain their pre-reflective or un-thematized nature. However, that would leave the culturally specific value that these objects have for their users unaccounted for, since sacred objects are simultaneously instruments of thought and objects of thought. That is what makes them ‘symbolic’: as we think about them, they take us to another form of reality. And yet there is nothing mysterious in these symbolic languages, just as there is nothing mysterious or ‘unnatural’ in the supernatural itself, as long as we do not translate them into propositional language. Sacred objects are uncanny, baffling and enigmatic because we cannot find a theory that accounts for their sacred nature. But we cannot find that theory because there is no such theory other than the object itself and the set of interwoven modes of experience that place it into a meaningful totality.»

(Carles SALAZAR, Understanding sacred objects: Towards an anthropological theory of religious meaning, «Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford Online», 2019, vol. 11, núm. 1, p. 53-68)